Mapping the Long Trail: the best is now free with OpenStreetMaps

2021-07-01On January 24, 2010, Zeke Farwell completed the Long Trail. He had begun just two days earlier, connecting more than 50 segments of trail spanning over 200 miles. Motivated by “the longest and most well known hiking trail in Vermont”, Zeke often revisited portions of the trails in the years to come.

Now I’m not revealing a secret FKT, but rather the completion of the Long Trail route on OpenStreetMap. OpenStreetMap is like Wikipedia but for maps: a collaborative project to create a free editable map of the world.

When I got in touch with Zeke, he wrote “I started contributing to OpenStreetMap in 2008 largely because good online trail maps were hard to come by at the time.” Due to the efforts of contributors like Zeke — most volunteers, exceeding 6 million in number — OpenStreetMap has begun to rival, and often exceed, proprietary alternatives like Google Maps.

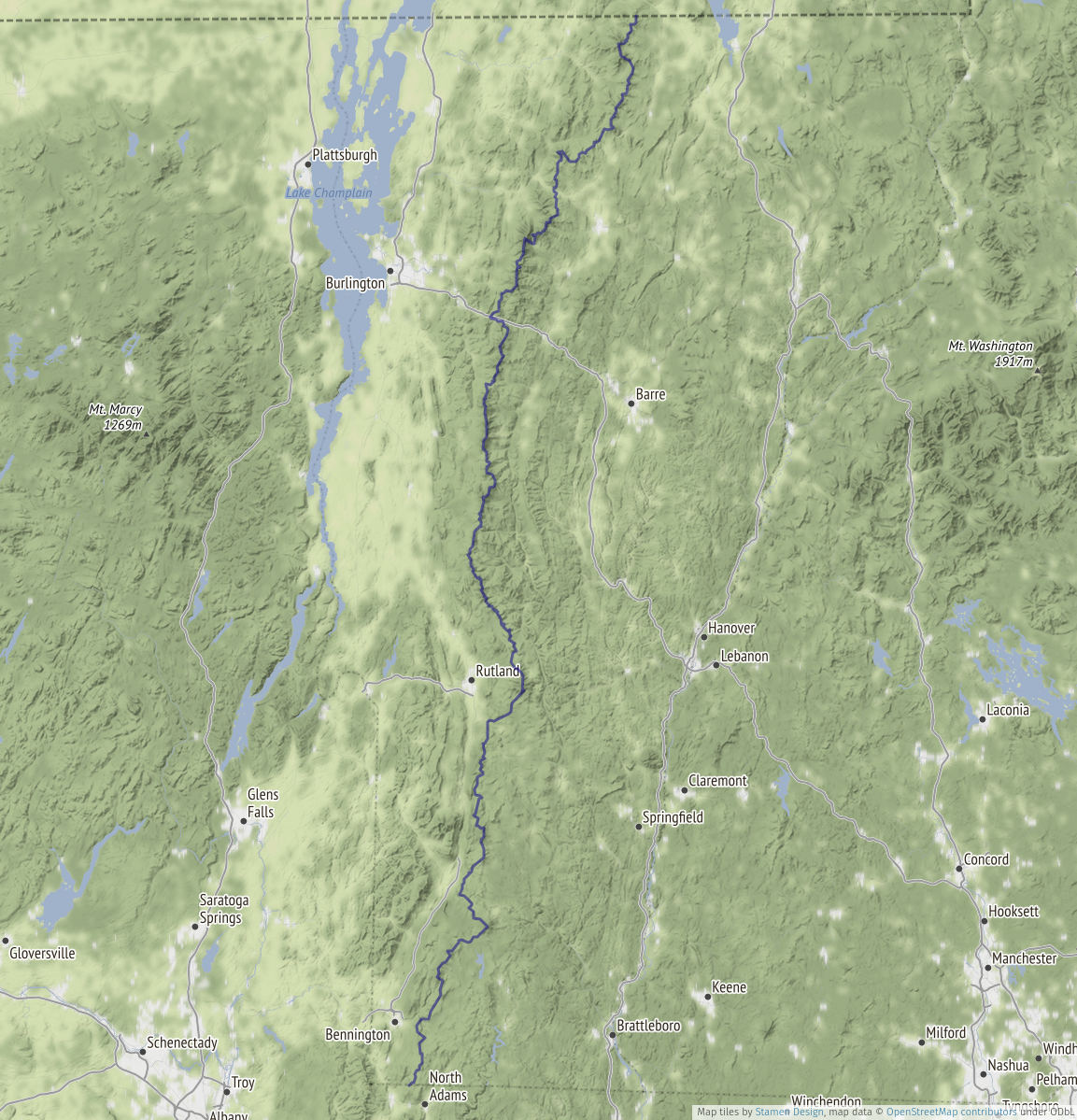

I write this post to announce that the best map of the Long Trail is now freely available to anyone via OpenStreetMap. Curious where the oldest long-distance hiking trail in America wanders? Look no further than OpenStreetMap.

The Big Three

My interest in mapping the Long Trail began with my September 2020 southbound thru-hike. As far as navigation options for hikers go, there are three main mapmakers: Green Mountain Club, Guthook, and OpenStreetMap.

Green Mountain Club

The Green Mountain Club (GMC) is the non-profit organization that maintains the Long Trail. The GMC publishes a paper Long Trail map, last updated in 2021 and on its 6th edition. The map is plastic-coated for water resistance and divided into 8 sections to minimize refolding. It includes distances, major side trails, shelter locations, 100-feet contour lines, hill-shading, elevation profiles, and nearby towns at 1:85,000 scale. If you like a physical map, then consider supporting the GMC! The map is listed at $12.95, and available from major retailers like REI, Amazon, and your local outfitters.

The GMC also releases a digital version of their map, available via the Avenza mobile App for $12.99. With this map, you are essentially buying a georeferenced PDF of the paper map. This means you can use your phone’s GPS (which works in airplane mode) to superimpose your location on a static map. But the PDFs are locked in the Avenza app, so make sure you like the Avenza interface before purchasing.

Guthook Guides

Guthook Guides brands itself “the #1 app for long-distance hikes”. Currently, Guthook sells guides for 53 trails, including the Long Trail for the price of $11.99. The Guthook App includes the route and locations of shelters, campsites, water sources, and viewpoints.

The real selling point however is the large number of user comments on points of interest (POIs). The comments can help with scouting to optimize your hike, but also can distract from the experience, burn a hole in your battery pack, and create reliance on an information source that isn’t available for trails off the beaten path.

Guthook is made by hikers for hikers. But its database of routes and POIs is proprietary. Leaving a comment or suggesting a new POI is sharing that information only with customers of Guthook, rather than society at large.

OpenStreetMap

Unlike the proprietary Google or Apple Maps, anyone is free to reuse and modify OpenStreetMap. This has resulted in a diverse range of contributors and consumers. Tesla owners have added missing parking lots to improve their cars’ Smart Summon autonomous parking feature. Amazon updates roadways and adds missing driveways to improve their delivery logistics. The Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team applies the map to assist with disaster response. Popular navigation apps like Strava and MapMyRide show their users maps derived from OpenStreetMap. I’ve even used it to navigate through Africa.

OpenStreetMap has a lot more than just streets, and contains natural features as well as those related to outdoor recreation, such as trails, campsites, shelters, waterways, and cliffs. Unlike the GMC map and Guthook, OpenStreetMap is not based around any single trail. Nonetheless, it contains the entire Long Trail. But since OpenStreetMap itself is just a geospatial database, it is best paired with an outdoor navigation app that specialize in rendering wilderness.

The website Waymarked Trails allows you download the trail as GPX or KML, such that you could load it into your favorite navigation app — popular ones include Strava, Gaia GPS, CalTopo, AllTrails, ViewRanger, Outdooractive, and Komoot. All of these apps include data from OpenStreetMap in their default map rendering. So by exporting the Long Trail to a route and uploading it to these apps, we’re essentially highlighting a trail that should already be on the map. Many of these apps support downloading maps for offline use, but sometimes only as a paid feature.

If you just want to look at the Long Trail route from OpenStreetMap quickly, here’s an embedded map from uMap:

Comparison

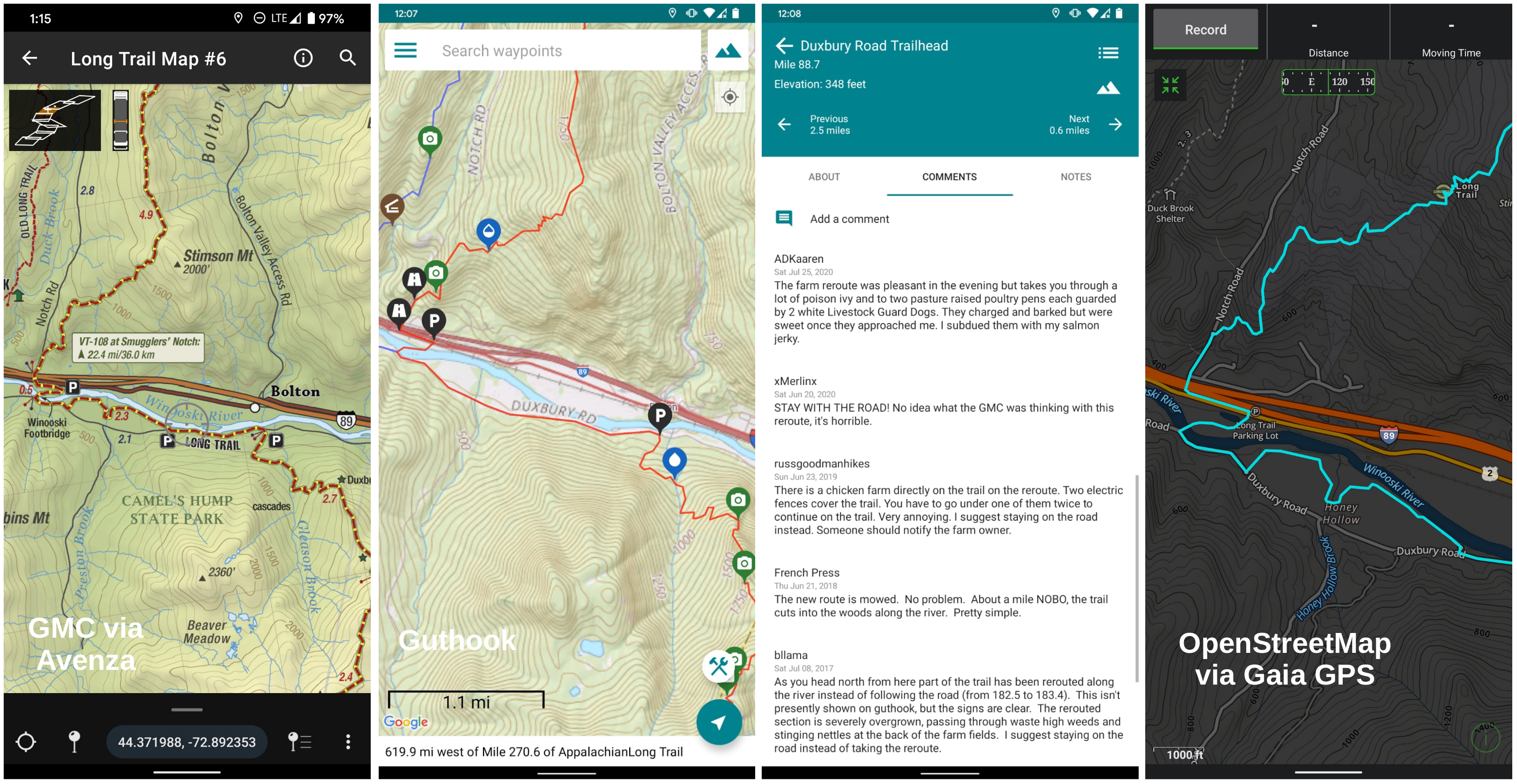

Here’s how the three maps look on mobile. With both GMC/Avenza and Guthook, you’re required to use their selected map as the background. If you look closely at the Guthook screenshot, you’ll see the map is from Google. For an OpenStreetMap-derived map, we can use any of the options above. Here, Gaia GPS is used with their dark mode map.

I picked a landmark segment of the trail, which passes over the Winooski River and under Interstate 89, coinciding with the lowest elevation point along the hike. One difference between the maps is that Guthook skips a part of the trail, staying on Duxbury Road instead. If you look at the comments on Guthook for the nearby trailhead, many users note the new-and-true route. This is a good example of how Guthook comments provide advanced reconnaissance, but can diminish the experience should they spoil the surprise of a guard dog ambush or tempt you to yellow blaze.

My Hike

I hiked the Long Trail in September, with my two friends Freshmeat and I.A.O. Moosalamoo (trail names). September is an ideal month, since there are fewer bugs, less mud, and later sunrises. But really any month is a good time to hike! We hiked 280 miles over 12 days, 22 hours, and 42 minutes, taking us from Canada to Massachusetts along the spine of the Green Mountains.

It’s hard to sum up the trip in three photos. But I’ll try.

The trail hits many of Vermont’s most prominent ski areas, including Stratton (detour), Bromley, Killington (recommended detour), Pico (detour), Middlebury Snow bowl, Sugarbush, Mad River Glen, Stowe, Smuggler’s Notch, and Jay Peak. Here Freshmeat enjoys the morning fog on Lift 2 of Mad River Glen:

After a grueling day that started in Johnson and ended at the Taft Lodge on Mount Mansfield, I prepared a deluxe feast for all.

The next morning, we were rewarded by an unremarkable, windy, and solitary sunrise on Vermont’s highest peak. There were some incredible beaver dams along the path, including the one that created this pond where we stayed on our last night (see also the astrophotography version).

If you’d like to see more pictures from our hike or explore the route further, here are the daily recordings on Strava:

- 2020-09-12 Long Trail Day 1

- 2020-09-13 Long Trail Day 2

- 2020-09-14 Long Trail Day 3

- 2020-09-15 Long Trail Day 4

- 2020-09-16 Long Trail Day 5

- 2020-09-17 Long Trail Day 6

- 2020-09-18 Long Trail Day 7

- 2020-09-19 Long Trail Day 8

- 2020-09-20 Long Trail Day 9

- 2020-09-21 Long Trail Day 10

- 2020-09-22 Long Trail Day 11

- 2020-09-23 Long Trail Day 12

- 2020-09-24 Long Trail Day 13

- 2020-09-25 Long Trail Finale

Editing the Map

According to the US Forest Service, the Long Trail is #1 (or perhaps #3). But according to OpenStreetMap, it’s 391736. That is the ID for the Long Trail relation. The relation connects all the individual trail segments (called ways) into a single conceptual unit.

When I mentioned Zeke Farwell completing the Long Trail, I was referring to the relation which created a continuous path the length of Vermont. Zeke described a bit more about his early work on the Long Trail:

I imported most of the trail from a publicly available government data source so it would have been “complete” from end to end right away. This imported trail was better than nothing, but not very accurate so for the next few years I refined it from my own GPS traces, aerial imagery, or any other data sources I came across.

He went on to complete the trail physically in 2012. Eight years later, when I hiked the trail with a copy of the OpenStreetMap relation loaded into my navigation app, I noticed some portions of the trail were off. And many side trails were missing. Many of the trails still followed Zeke’s original imports, and hadn’t yet benefitted from a decade of increased data and improved GPS accuracy.

So I set out to revise the entire Long Trail. Over a third of the Long Trail is shared with the Appalachian Trail. I expected the Appalachian Trail portion to be more accurate due to its significance, but this was not the case.

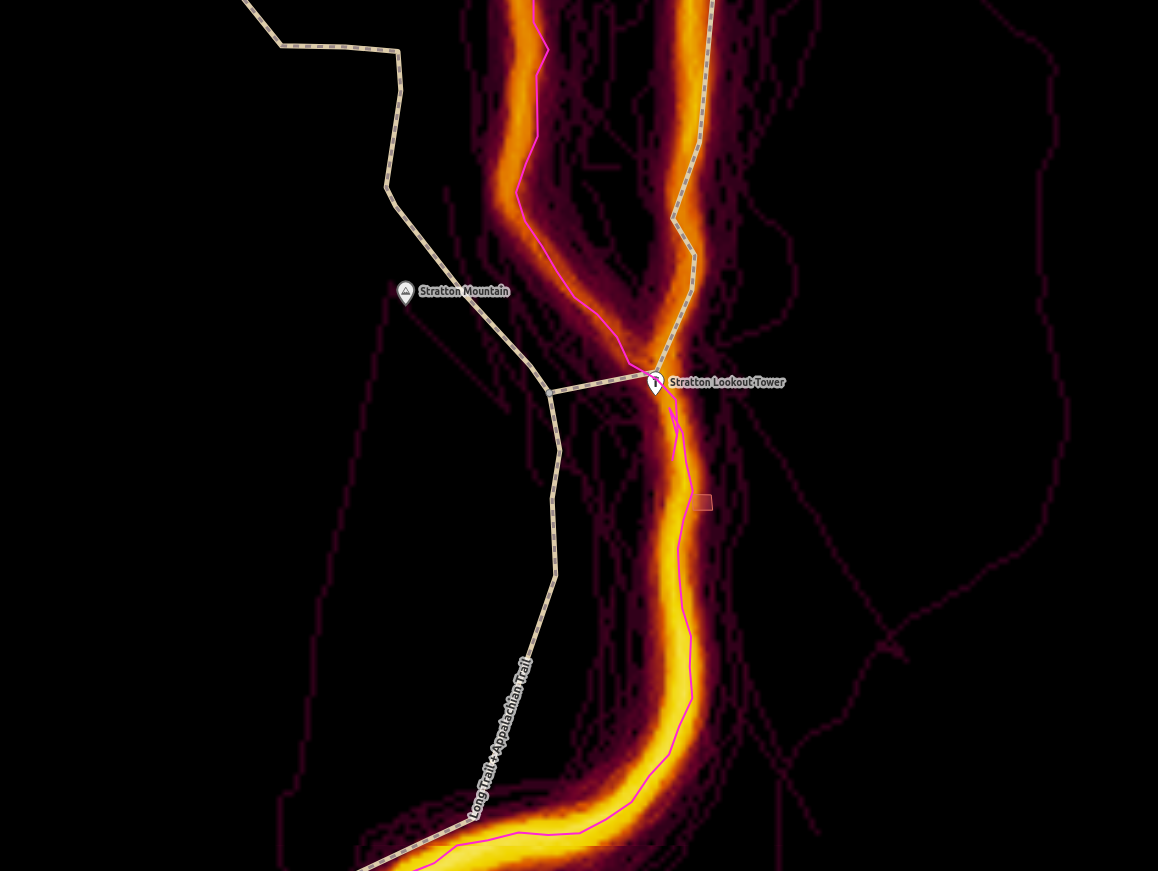

I based my mapping primarily on GPS tracks. First I had my own track from our thru-hike, and second I could reference the Strava heatmap, which summarizes all tracks uploaded to that platform over the past two years.

I used the online iD editor for all of my edits (except for rearranging the relation members which I had to do with JOSM). Here is an in-progress edit of the summit of Stratton Mountain. The dashed lines show the trails in OpenStreetMap. The red/orange/yellow heatmap shows the tracks of Strava users. The pink line is my track.

Any GPS recording from consumer hardware will have some inaccuracy, but this is easily overcome by averaging many tracks! Wisdom of the crowd. My track as well as the Strava heatmap make it clear that the Long Trail needs to be shifted east, along with some other alignments. I made these changes in changeset 91733004, where I also added additional metadata to the fire tower like that its height is 21 meters. Maybe now the tower will show up in flight simulators. By the way, if you like fire towers, the Long Trail has three: Glastenbury, Stratton (enclosed), and Belvidere.

In total, I made 34 changesets (collections of edits) related to the Long Trail. I started the edits the day after getting back from the hike, and completed my revisions in 11 days, faster even than we hiked it! Warning before you start contributing to OpenStreetMaps, it can be addicting.

I added many of the shelters that were missing, such as the Duck Brook Shelter on the Old Long Trail that’s visible in the map comparison image above. One type of feature that is still largely missing is privies. While all the shelters have a privy nearby, it can be surprisingly hard to find them, especially at night. Here’s a privy at Battell Shelter added recently by user dchiles. How is this coded in the database? It is just a point (node) that has the following tags:

| tag | value |

|---|---|

| access | yes |

| amenity | toilets |

| composting | yes |

| toilets:disposal | pitlatrine |

| toilets:handwashing | no |

I added the composting=yes tag to help raise awareness of proper privy etiquette:

no trash, only toilet paper and poo, unless it’s a moldering privy in which case urine is welcome.

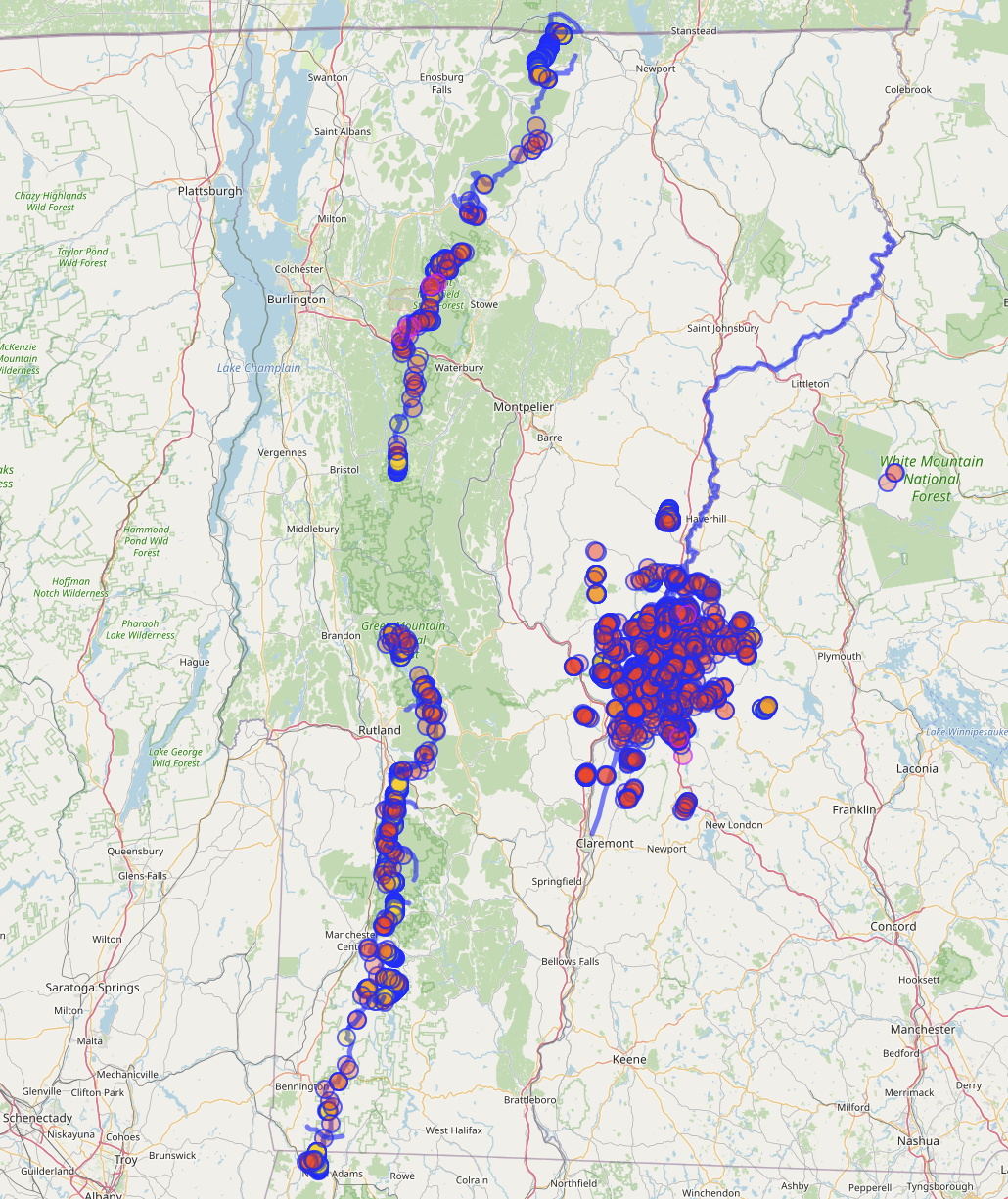

On the interactive map above, there is a before layer you can toggle on, which will show the Long Trail route before my edits. While only a few sections deviated in major ways, I realigned large portions of the trial. Looking at features (specifically nodes, ways, and relations) that were last edited by me, you’ll notice a pattern in my contributions spanning the Long Trail (along with the Upper Valley, see also YOSMHM):

Do you see the section in the middle — in Green Mountain National Forest — where I don’t have any of the most recent edits? That is because another user Adam Franco made further enhancements more recently.

That is the beauty of OpenStreetMap. It is a living map, whose model of open licensing and crowdsourced contribution give rise to a map more complete and encompassing than any proprietary alternative.

Liberate the trails, put them on the map!

Find supplementary materials to this blog post at https://github.com/dhimmel/long-trail-maps.